The Fallen Angel Painting: Lucifer’s Iconic Portrayal

Picture a figure of celestial splendor, his once-glorious wings now crumpled, his piercing gaze clouded with a single tear of rage and sorrow. This is the vision of Lucifer captured in Alexandre Cabanel’s 1847 masterpiece, The Fallen Angel Painting. Created when the artist was just 24, this work is a bold departure from conventional depictions of the Devil, presenting him not as a grotesque villain but a tragic, almost heroic figure. Rooted in literary inspiration and executed with stunning technical skill, the fallen angel painting shocked the art world of its time and continues to resonate today. In this article, we’ll explore the artist’s background, the painting’s literary origins, its rich symbolism, the controversy it ignited, and its enduring legacy.

The L’Ange Déchu — The Angel Who Refused to Stay Down

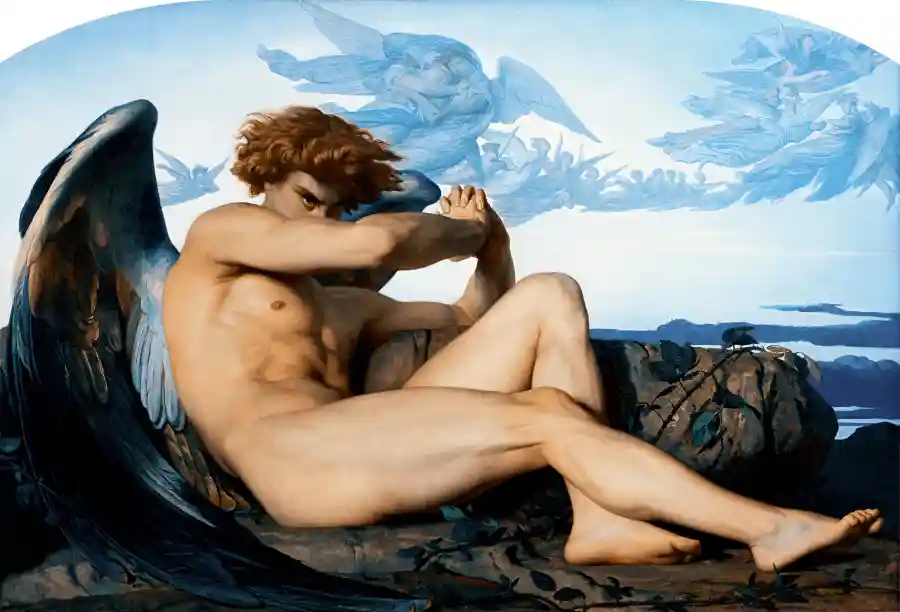

There’s something unforgettable about L’Ange Déchu, or The Fallen Angel. It might just be one of the most hauntingly beautiful — and emotionally charged — artworks ever painted. A nude angel, wings outstretched, crouches in sorrow. He hides his face behind trembling arms, a tear of rage and heartbreak sliding down from bloodshot eyes. His hair whips in the wind, his body sculpted to perfection — every muscle coiled, tense with silent defiance. This isn’t defeat. This is the pause before rising.

It was 1847, and a 24-year-old Alexandre Cabanel had already made waves in the world of French academic painting. He joined the École des Beaux-Arts at 17, debuted at the Paris Salon by 21, and claimed the elite Prix de Rome at just 22. Early on, he played by the rules — painting somber biblical scenes that aligned with traditional expectations. His Salon piece featured a mournful Christ in The Guardian of Olives, and his award-winning Rome entry showed Jesus standing trial before Pontius Pilate. Technically masterful? Yes. But emotionally? Something was missing. Christ, in Cabanel’s hands, looked oddly untouched by the pain.

Was he simply following the script the Salon preferred — a calm, dignified Savior? Or was he too cautious to let emotion bleed through the canvas?

Then came 1846 — and a turning point. Cabanel painted Orestes, son of Agamemnon, in a bold, large-scale nude inspired by Greek tragedy. It was powerful. It was risky. And it was rejected. Brutally. Critics called it “oversized and inept.” A hard blow for an artist on the rise.

But instead of shrinking back, Cabanel returned with fire — quite literally. Enter the angel you can’t look away from.

Drawing inspiration from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Cabanel reimagined the moment of divine exile not as defeat, but as defiance. Among Milton’s five fallen angels — Moloch, Belial, Mammon, Mulciber, and Beelzebub — Cabanel chose the latter, who over time has become synonymous with Lucifer. This was not just any angel. This was the angel — the one who dared to question, to rebel, to fall.

The Salon wasn’t ready. The judges were stunned, and not in a good way. According to Sybille Bellamy-Brown in Procès-verbaux de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts, their verdict was brutal: “The movement is wrong, the draughtsmanship imprecise, the execution deficient…” And to make matters worse, they accused it of being too romantic in style — too much passion, too much feeling.

Frustrated, Cabanel vented in a letter to his patron Alfred Bruyas: “That’s my reward for all the trouble I gave myself not to submit an average piece of work…”

It would take another three years and the success of his Death of Moses to win the critics back. But let’s be honest — the spark was already lit. L’Ange Déchu was Cabanel’s true awakening. A masterpiece born from rejection, rebellion, and raw emotion.

Because that’s where the magic begins — not in perfection, but in passion. Not in victory, but in the fall.

Was he simply following the script?

Did Salon preferred — a calm, dignified Savior? Or was he too cautious to let emotion bleed through the canvas?

Then came 1846 — and a turning point. Cabanel painted Orestes, son of Agamemnon, in a bold, large-scale nude inspired by Greek tragedy. It was powerful. It was risky. And it was rejected. Brutally. Critics called it “oversized and inept.” A hard blow for an artist on the rise.

But instead of shrinking back, Cabanel returned with fire — quite literally. Enter the angel you can’t look away from.

Drawing inspiration from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Cabanel reimagined the moment of divine exile not as defeat, but as defiance. Among Milton’s five fallen angels — Moloch, Belial, Mammon, Mulciber, and Beelzebub — Cabanel chose the latter, who over time has become synonymous with Lucifer. This was not just any angel. This was the angel — the one who dared to question, to rebel, to fall.

The Salon wasn’t ready. The judges were stunned, and not in a good way. According to Sybille Bellamy-Brown in Procès-verbaux de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts, their verdict was brutal: “The movement is wrong, the draughtsmanship imprecise, the execution deficient…” And to make matters worse, they accused it of being too romantic in style — too much passion, too much feeling.

Frustrated, Cabanel vented in a letter to his patron Alfred Bruyas: “That’s my reward for all the trouble I gave myself not to submit an average piece of work…”

It would take another three years and the success of his Death of Moses to win the critics back. But let’s be honest — the spark was already lit. L’Ange Déchu was Cabanel’s true awakening. A masterpiece born from rejection, rebellion, and raw emotion. Because that’s where the magic begins — not in perfection, but in passion. Not in victory, but in the fall.

Alexandre Cabanel: The Master Behind the Canvas

To appreciate the fallen angel painting, we must first understand its creator. Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889) was a leading figure in 19th-century French Academic art, a style that prized precision, classical themes, and polished execution. Born in Montpellier, France, Cabanel showed early promise, entering the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris at age 17. His talent earned him accolades and patronage from the highest levels of society.

Key Milestones in Cabanel’s Career:

- Won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1845, securing a five-year residency in Italy.

- Became a favored artist of Emperor Napoleon III, who admired his elegant, sensual works.

- Gained fame with pieces like The Birth of Venus (1863), a celebrated example of his ability to merge beauty with mythology.

Cabanel’s academic training and refined style set the stage for his Lucifer painting, in which he blended technical mastery with emotional daring.

Literary Roots: Milton’s Paradise Lost

The inspiration for the fallen angel painting lies in John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost (1667), a retelling of the biblical fall of Lucifer. Milton’s Lucifer is no mere demon; he’s a charismatic rebel whose pride leads to his banishment from Heaven. Cabanel seized on this complexity, depicting the moment just after Lucifer’s fall—a scene of defiance and despair.

Milton’s Influence:

- In Paradise Lost, Lucifer declares, “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven,” a line that echoes in the painting’s proud yet broken figure.

- The poem’s focus on Lucifer’s inner conflict—ambition warring with regret—mirrors the emotional depth of Cabanel’s Lucifer painting.

By translating Milton’s words into visual form, Cabanel crafted a work that invites viewers to grapple with the duality of beauty and ruin.

Decoding the Symbolism in The Fallen Angel Painting

The Fallen Angel Painting is a tapestry of symbols, each element carefully chosen to convey meaning. Lucifer’s physicality, expression, and surroundings tell a story of rebellion and its aftermath.

Lucifer’s Form:

- His muscular, almost sculptural body reflects his former divine status, now marred by his fall.

- A tear glints in his eye, symbolizing anger and a flicker of remorse.

- His arms shield his face, a gesture of shame tinged with stubborn resistance.

The Setting:

- The rocky ground beneath him contrasts with the ethereal sky, marking his exile from paradise.

- Distant angels, bathed in light, gaze down with a mix of sorrow and condemnation, amplifying his isolation.

Color and Light:

- Lucifer’s pale, glowing skin stands out against the darker tones, emphasizing his otherworldly beauty.

- The interplay of shadow and light heightens the drama, a hallmark of Cabanel’s academic style.

These symbols weave a narrative of loss, pride, and the cost of defiance, making the Lucifer painting a study in emotional contradiction.

A Stir at the Salon: Controversy and Reception

When the fallen angel painting debuted at the Paris Salon in 1847, it was a lightning rod for debate. The Salon, a bastion of tradition, wasn’t prepared for Cabanel’s audacious take on a biblical villain. Exhibited during his time in Rome as a Prix de Rome scholar, the work broke from the expected classical subjects.

Contemporary Reactions:

- Some hailed its technical brilliance, with one critic noting, “The vigor of the composition is undeniable.”

- Others balked at its romanticism, decrying it as overly theatrical or morally ambiguous.

- The choice to depict Lucifer—an unprecedented move for a student submission—unsettled the conservative judges.

Though polarizing, the painting cemented Cabanel’s reputation as an artist willing to push boundaries, paving the way for his later triumphs.

Legacy and Influence on Art and Culture

The Fallen Angel Painting has transcended its era, leaving a lasting imprint on art and popular imagination. Its portrayal of Lucifer as a figure of tragic beauty challenged norms and inspired a wave of creative reinterpretation.

Artistic Influence:

- Symbolist artists like Fernand Khnopff drew from its emotional intensity and focus on the sublime.

- The painting’s dramatic lighting influenced cinematic techniques in later visual storytelling.

Cultural Echoes:

- The Lucifer painting has appeared in modern media, from book covers to film references, symbolizing rebellion and existential struggle.

- Its image graces tattoos and artworks, a testament to its enduring appeal.

Today, the fallen angel painting is housed at the Musée Fabre in Montpellier. It remains a touchstone for those exploring the interplay of beauty and downfall.

Also read:

- Painting with a Twist: How Breaking the Rules on Canvas Keeps Art Alive

- Fun 10 things to draw when bored: Beginner-Friendly Instant Inspiration

- A Beginner’s Guide to the loomis method – Creating Lifelike Faces

- lippan art design and Its Evolution: A Heritage of Reflection and Creativity

- Modern texture paint designs: The Fusion of Art and Innovation

Conclusion: The Timeless Allure of The Fallen Angel Painting

More than a century and a half after its creation, The Fallen Angel Painting by Alexandre Cabanel continues to captivate and provoke. Its fusion of Milton’s literary depth, striking symbolism, and technical prowess offers a window into the complexities of human nature—pride, defiance, and the bittersweet taste of freedom. Whether viewed as a masterpiece of academic art or a bold reimagining of a biblical tale, the fallen angel painting is a powerful reflection of our fascination with the fallen and the divine. It invites us to ponder: what does it mean to fall, and can beauty persist in ruin?