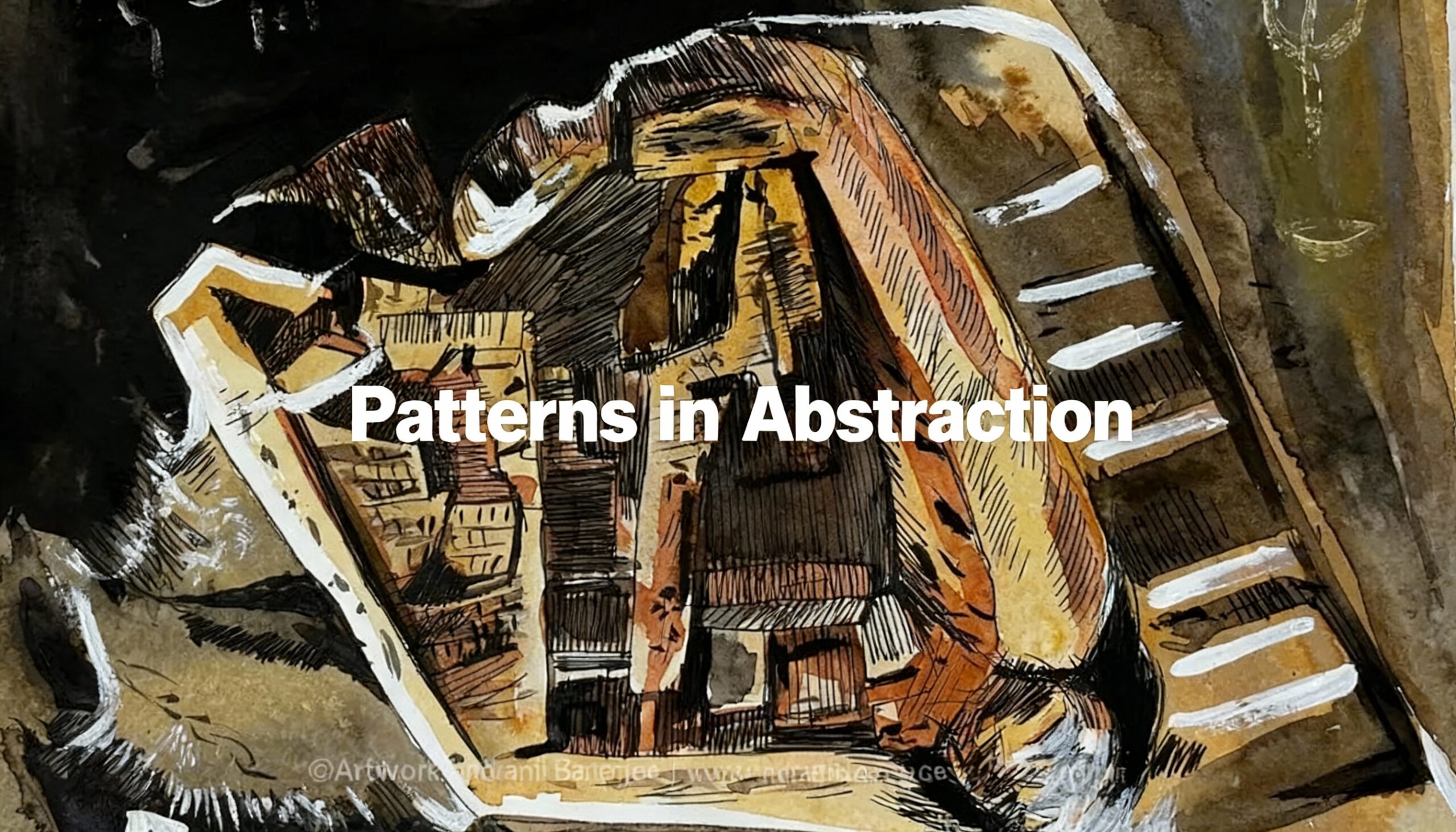

Relatable famous abstract art: Patterns in Abstraction

Viewers often approach famous abstract art with curiosity and hesitation. They stand before complex colors and forms, searching for something known. When they notice even a hint of a face, an animal, or a landscape, their hesitation drops and a connection appears.

This response does not occur by accident. It follows a clear visual and psychological logic that artists can design with intent. The patent theory of relatable abstraction explains how familiar geometrical positioning guides the eye toward recognition inside apparent chaos.

Pareidolia plays a central role. The human brain hunts constantly for known patterns. Artists who respect this instinct can build abstract surfaces where discovery feels natural, not forced.

Why famous abstract art Needs Relatable Anchors

Viewers still ask what is abstract art and struggle with any strict abstract art definition. They expect either total freedom or total confusion. In reality, abstraction can balance mystery with recognition.

If an artist only rejects reality, many viewers disengage. They see decoration, not depth. Relatable abstraction proposes another path. It keeps the liberty of distortion while preserving subtle anchors from human anatomy and everyday objects.

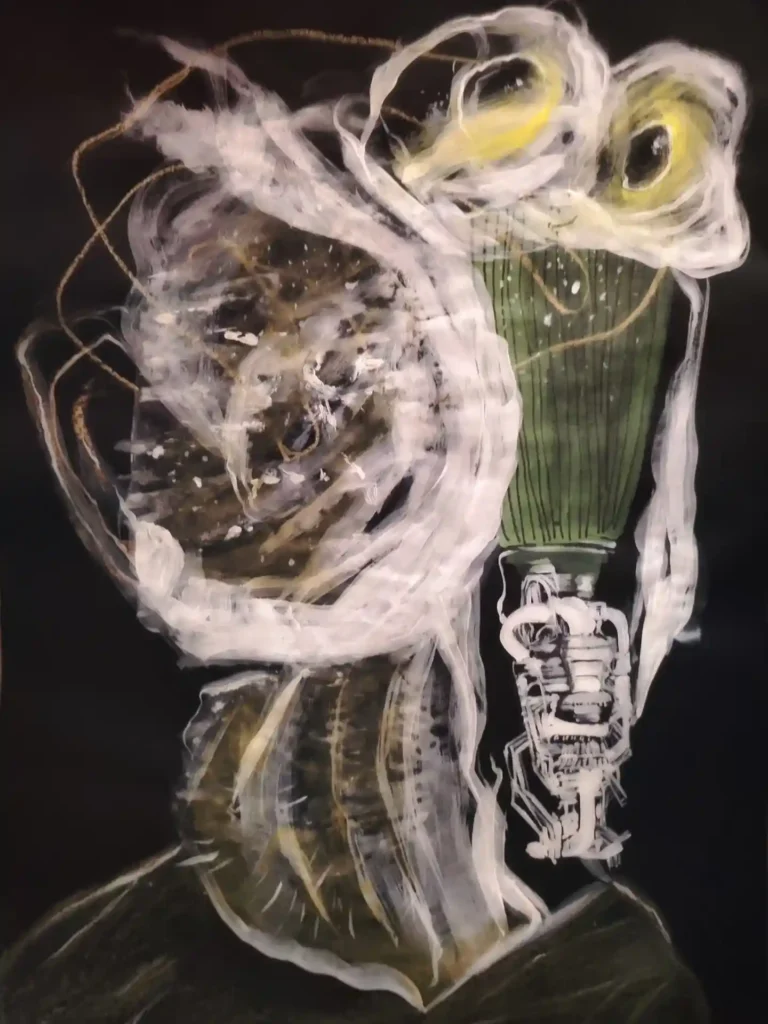

The theory positions these anchors carefully. Eyes remain in an eye-zone, a mouth sits below, a wing-like shape tilts as if ready for flight. No literal illustration appears, yet the structure feels correct.

The Psychology Behind famous abstract art and Recognizable Forms

This method aligns closely with Gestalt perception. The mind joins scattered marks into coherent wholes. When shapes occupy familiar locations, the viewer reads them as hidden portraits, bodies, or creatures.

Pattern recognition evolved as a survival tool. The same mechanism now guides how audiences read paintings. A curve suggests a shoulder. A triangle leans where a nose should stand. Circles cluster where eyes usually rest.

These quiet cues reduce the distance between artwork and observer. The painting invites participation. The viewer enjoys solving a visual puzzle instead of facing a closed, unreadable surface.

Designing famous abstract art with Familiar Patterns

Relatable abstraction does not dilute abstraction. It organizes it. Artists start from essential geometries of known forms. They break a face into ovals, arcs, and lines, then shift, stretch, or layer them.

The key lies in maintaining relational order. Eyes remain roughly parallel. The nose still anchors the vertical center. The mouth keeps its place below. Even when color vibrates and edges fragment, the viewer senses a presence.

The same approach applies beyond the figure. A village hut turns into a character when windows behave like eyes and a door becomes a nose. An arrangement of planes suggests a bird because one angled form reads as a wing and another as a head. Abstraction grows from recognition, not away from it.

How Viewers Read famous abstract art in Personal Ways

When people notice such patterns, they project memory onto them. One face recalls a stranger from a train, another recalls an ancestor. No explicit likeness exists, yet emotional truth emerges through geometry.

This process deepens engagement. The viewer slows down, tracks alignments, tests interpretations, and experiences small moments of discovery. That cognitive effort produces attachment and longer attention spans.

Because forms stay open, interpretations remain plural. Each spectator arrives with different histories and finds different images. The painting becomes a shared ground between the artist’s internal vision and the audience’s inner archive.

The Patent Logic Inside famous abstract art

The patent-based framework formalizes these observations into a repeatable method. It instructs artists to map human or animal anatomy through abstracted yet accurate positional cues.

Hands become arrangements of elongated blocks, but each finger still radiates from the right joint. Torsos fracture into planes, but the head still crowns the vertical axis. Even fluid, gestural marks can echo these distributions.

The system also welcomes non-living analogies. When architectural or mechanical forms echo bodily geometry, viewers read life into them. The bridge looks like a spine. The tower suggests a standing figure. Recognition arises through configuration, not detail.

This structure respects both expression and communication. The artist releases emotion through color, texture, and rhythm. At the same time, the work speaks clearly enough for viewers to enter without instruction.

Relatable Abstraction and the Future of famous abstract art

Relatable abstraction answers a central tension within contemporary practice. Many artists desire freedom from strict representation. Many audiences, however, still seek a path into complex images.

By embedding familiar patterns through deliberate geometrical positioning, artists honour both needs. They invite psychological agreement instead of conflict. They harness pareidolia, Gestalt grouping, and memory to guide response.

This approach does not simplify ideas. It sharpens them. When abstract compositions carry subtle yet recognizable structures, they gain clarity, accessibility, and emotional weight. In that balance, famous abstract art maintains its experimental spirit while remaining deeply human, allowing every viewer to recognize a part of their own world inside its shifting forms.